While modern finance and international banking have grown intricate and prestigious, their roots lie in more straightforward, human-centered origins. The guiding principles of futures markets, options, and global commerce are not new concepts; they trace back to ancient civilizations.

Long before Wall Street or the Chicago Board of Trade existed, early communities engaged in advanced practices of risk transfer, speculative pricing, and contract-based trading, with agriculture being the focal point. The unpredictability of nature necessitated foresight, collaboration, and trust-based relationships to navigate future outcomes.

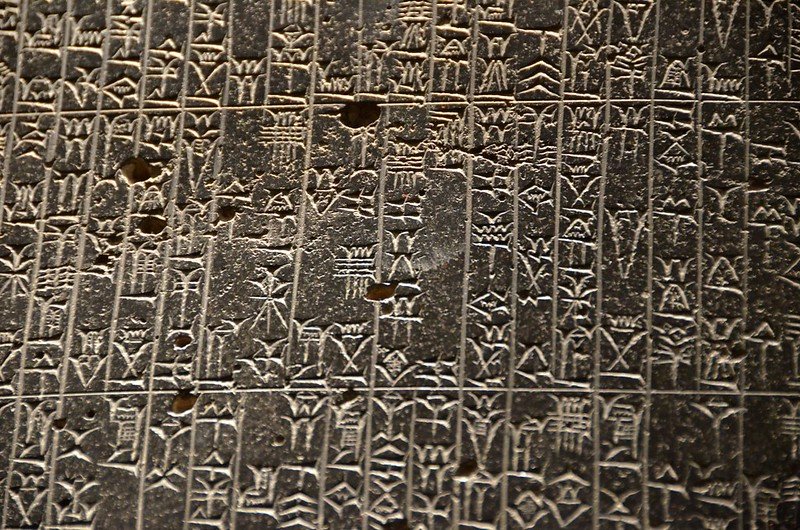

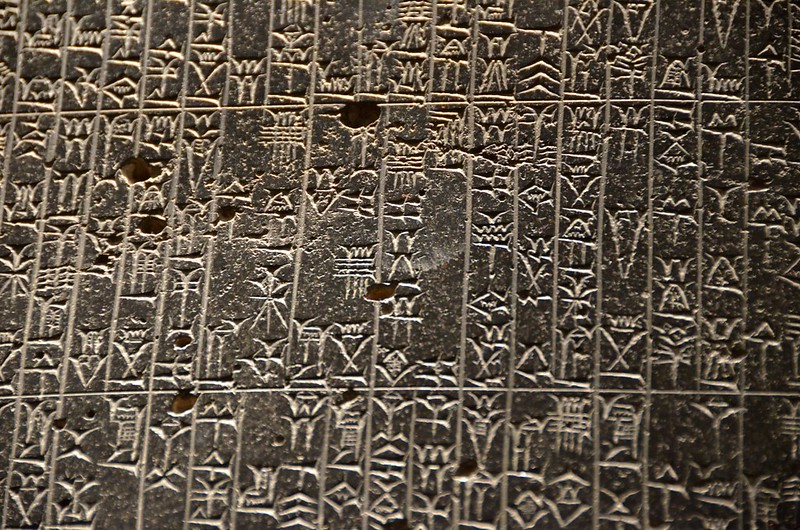

A notable instance of primitive finance is found in Genesis 41, where an Egyptian Pharaoh’s dream forecasts seven years of prosperity followed by seven years of famine. Joseph interprets this vision and proposes a state-run commodity strategy: a 20% tax during the abundant years, with reserves saved for sale during the famine. This approach not only helped Egypt endure but also allowed it to profit by exporting grains to nearby nations. This biblical tale illustrates the logic behind commodity speculation and reserves management. Additional financial innovations can be seen in the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1750 BCE), which details contracts for future delivery at predetermined prices, marking some of the earliest forms of futures and options agreements. These legally binding contracts were stored in temples, making them akin to early modern clearinghouses in Mesopotamia.

In ancient Greece, Aristotle recounts the tale of Thales, a philosopher who secured exclusive rights to olive presses, anticipating a fruitful harvest much like an early options trader. Similarly, Ancient Rome utilized forward contracts in grain markets, along with maritime loans (foenus nauticum) and a network of argentarii (bankers) who provided deposits, loans, and credit in marketplaces. The Phoenicians excelled in Mediterranean trade, developing joint-risk maritime ventures—similar to early equity investments—which allowed merchants to pool resources for shipping endeavors, sharing both profits and risks. These early systems laid the foundation for modern banking, insurance, and structured finance.

From Mesopotamia to Egypt, Greece, Rome, and Phoenicia, humans have continually sought methods to derive value from time, trust, and risk. Agriculture, characterized by its seasonal rhythms, extended timelines, and inherent uncertainties, became a crucible for financial innovation. The principles established through ancient practices continue to influence today’s futures markets, derivatives, and asset management systems, even though their original spiritual and practical contexts often go unrecognized.

Templar Banking and International Trade Networks

Anthropology reveals that in the early phases of known history, ancient societies operated within a “gift economy”. This system was based on the reciprocal exchange of goods and services, guided by social norms and customs. Such non-market exchanges were facilitated by established social practices.

The renowned Knights Templar, under the Order of the Temple of Solomon, ran its own sovereign economy designed for the benefit of the people and sustained by a meritocratic framework. The Medieval Knights Templar aimed to restore an ancient spiritual economy of merit coins within a system of chivalric favors, empowering individuals to reclaim human rights against power abuses. More than just warrior monks, the Templars were innovators of a moral financial system grounded in ethics, trust, and honor.

They developed one of the most sophisticated and secure transcontinental financial networks of medieval times, relying on a moral currency system. Religious coins served as symbolic tokens of moral merit, embodying acts of chivalry, spiritual service, and ethical behavior. Unlike secular currencies used for taxation and trade, these coins were measured not by fixed monetary value but by the trust and worth within a closed, spiritual economy. Each coin represented a favor given, received, or owed, allowing non-monetary exchanges of privileges, access, and protection, particularly for travelers and followers.

To support this moral economy and safeguard pilgrims, the Templars established an early version of secure, international banking infrastructure. They built depository outposts (fortified monasteries) throughout Europe and the Holy Land, serving as financial centers. Pilgrims could deposit funds in cities like London or Paris, obtain a letter of credit, and redeem it in Jerusalem, minimizing the risks of carrying physical wealth through unsafe regions. These hubs acted as trust nodes, providing vault security, asset custody, and transaction records. The system became so dependable that European royalty and Popes entrusted the Templars with their riches, funding military campaigns, crusades, and church activities through their network.

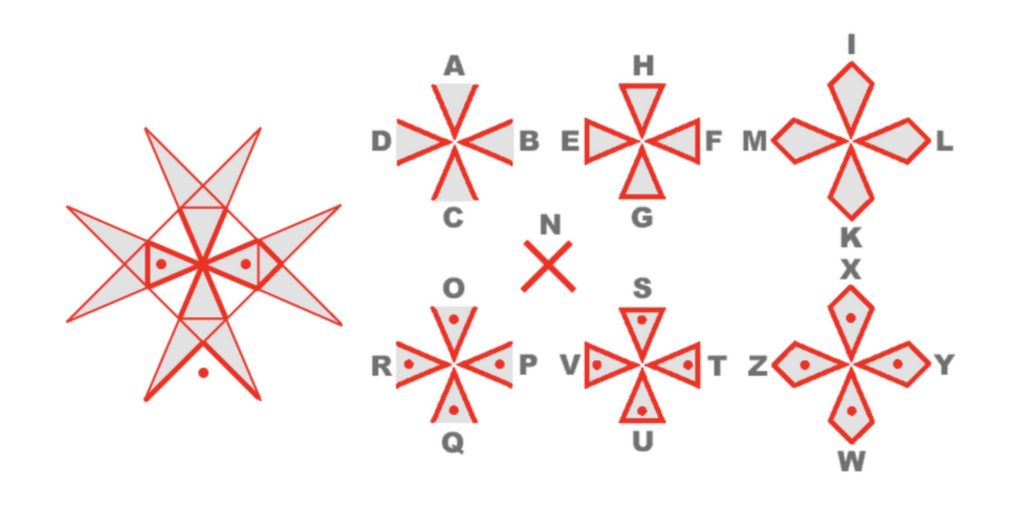

The innovations introduced by the Templars laid the groundwork for modern banking practices, including letters of credit (paving the way for modern checks and promissory notes), encrypted communications (using ciphers based on the Maltese cross for secure information transfer), dual-ledger systems (to manage deposits, withdrawals, and obligations across various territories), and asset security through vaults (their fortified temples served as secure storage for nobles, pilgrims, and institutions). The Templars’ system demonstrated that value could be linked to conduct and honor rather than just state-backed currency.

Origins of Hedge Funds and Private Financial Networks

Simultaneously with the rise of modern spot and futures markets in the mid-20th century, a new type of financial enterprise began to emerge—one that would transform investment strategies and global capital flows. Driven by technological advancements in markets and a growing demand for returns that surpassed traditional benchmarks, the idea of alternative investments emerged, leading to what we now identify as hedge funds. In 1949, Alfred Winslow Jones, a financial journalist and sociologist, launched what is widely regarded as…

The origin of hedge funds can be traced back to a pioneering approach that combined long positions (investments in stocks expected to rise) with short positions (investments in stocks expected to fall). This strategy aimed to mitigate market risk while pursuing returns that were not tied directly to market movements. The innovator behind this concept also utilized leverage—which involves borrowing capital to enhance profits—and introduced a groundbreaking compensation scheme where fund managers received 20% of the profits. This model has since become a standard practice in the industry. This was a pivotal moment that challenged established banking and investment norms, ushering in a new breed of capital managers who sought to profit regardless of market conditions, laying the groundwork for contemporary asset management and financial advancements.

By the 1960s, hedge funds began to capture the attention of affluent individuals and institutional investors. These funds, once limited to stock investments, started exploring other areas like commodities, fixed income, and foreign exchange (forex), testing a variety of innovative strategies. This shift marked the transition of hedge funds from being niche investment options to significant players in global finance.

In the 1990s, widespread financial deregulation in developed countries opened doors for bolder strategies. Hedge funds continued to adapt, incorporating tactics such as arbitrage, corporate acquisitions, and global macro trading. Fund managers emerged as the new champions of capitalism—navigating borders, managing capital with precision, and earning substantial profits, sometimes reaching hundreds of millions or even billions annually. One notable instance is George Soros’s Quantum Fund, which in 1992 famously bet against the British Pound, causing the UK to exit the Exchange Rate Mechanism and netting $1 billion in just one day. This event, often referred to as the day Soros “broke the Bank of England,” showcased the immense power hedge funds could wield, demonstrating how their actions could impact global financial stability.

The 2000s were a mix of success and setbacks for the hedge fund industry. The downfall of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM)—founded by Nobel Prize-winning economists—exposed the perilous nature of excessive leverage and misplaced confidence in quantitative models, particularly in illiquid markets. At the same time, the dot-com bubble generated substantial profits for some funds while leading others to heavy losses as speculative investments in tech stocks surged and subsequently crashed. As the 2008 financial crisis approached, a select few hedge funds profited by betting against subprime mortgages, accurately forecasting the housing market crash, while the wider economy suffered massive losses. These events highlighted hedge funds’ dual role as both innovation engines and risk amplifiers in today’s financial landscape.

The 2010s saw the rise of a new trading style—high-frequency trading (HFT)—fuelled by advancements in technology, including high-performance computing, fiber-optic networks, and sophisticated algorithms. Often run by highly skilled “super coders” with expertise in fields such as physics and mathematics, these firms executed thousands to millions of trades within milliseconds, exploiting minor market inefficiencies for substantial profits. The primary goal of HFT was to enhance trading speed—entering and exiting positions faster than traditional institutions—while taking advantage of minute differences between buying and selling prices, a strategy known as latency arbitrage. This speed advantage, paired with superior technology and information access, granted HFT firms unparalleled edge, often described as a nearly guaranteed profit-making means. While HFT improved market efficiency and liquidity, it also sparked debates regarding equity, transparency, and the prioritization of speed over strategy in modern finance. Nonetheless, HFT symbolized a new financial epoch—where algorithms replaced intuition, machines overtook markets, and fractions of seconds dictated success.

Overall, hedge funds and high-frequency trading represent a broader legacy: the evolution of private financial communication networks. From early Mesopotamian traders utilizing temple records to Roman bankers with handwritten ledgers, and even the Knights Templar’s encrypted letters of credit, financial influence has historically favored those with faster, more secure, and more unique information channels. Today, HFT firms function within rapid, closed-loop systems based on proprietary data feeds, co-located servers, and algorithmic frameworks—effectively forming a modern digital version of the secret financial networks of the past. These systems not only analyze the market but also anticipate and shape it through superior access and positioning. In this light, hedge funds and HFTs are not merely market players; they serve as gatekeepers of a parallel financial infrastructure, where informational disparities offer a significant advantage.

The High Priests of Modern Finance

We now grasp the significance of asset management in a technology-driven world, as well as the evolution of money and assets management throughout history, shaped by economic theories, financial innovations, and technological progress. The finance manager’s role entails managing investment funds responsibly through strategic asset allocation, risk management, and wealth creation. Our exploration will trace the journey from Jones’s inaugural fund to the era of modern high-frequency trading, highlighting the most successful contemporary managers and their strategies for navigating financial markets in any situation.

Ray Dalio established Bridgewater Associates in 1975, focusing on macro investing, risk parity, and the revolutionary all-weather portfolio. This diversified strategy is crafted to perform well across varying economic conditions, including growth, recession, inflation, and deflation. Typically, it divides investments among stocks, bonds, commodities, and gold to balance risks and returns. By distributing assets across different classes that respond differently to economic shifts, the portfolio seeks to reduce volatility while ensuring stable growth.

In 1990, Ken Griffin founded Citadel, one of the initial electronic multi-strategy funds diversifying across various asset categories. It employs several core trading strategies, each enhancing the firm’s overall success. The equity long and short strategy involves buying undervalued companies and shorting those that are overvalued using fundamental analysis and quantitative models to exploit price inefficiencies. Citadel has pioneered in the quantitative and high-frequency trading sectors, leveraging algorithms and machine-learning-driven models to execute trades in mere milliseconds, profiting from market discrepancies, arbitrage opportunities, and statistical signals. Importantly, it serves as a major market maker, providing liquidity to financial markets by consistently buying and selling assets at quoted prices, profiting from the bid-ask spread, and ensuring smooth trading operations.

Jim Simons founded Renaissance Technologies, renowned for its “Medallion Fund,” the most profitable hedge fund ever, which has achieved returns of 66% before fees since 1988. The fund specializes in quantitative, algorithmic, and machine learning-based investing, employing mathematical models, statistical arbitrage, and machine learning techniques to uncover hidden patterns in market data that escape human detection. It is not reliant on market trends, swiftly making trades to minimize risk exposure.

Data sources such as satellite imagery, news sentiment analysis, and even weather trends.

Looking Forward: Reclaiming Purpose Beyond Money with Decentralized Legacy

From the dawn of civilization, societies including Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, and the Phoenicians laid the groundwork for modern finance with vital technologies and systems. They introduced concepts such as grain-backed receipts, early futures contracts, maritime trade credits, and temple banking — all early forms of what we recognize today as complex financial instruments. As Western civilization developed, establishments like the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) emerged, creating formal guidelines and innovations such as futures contracts, methods for price discovery, and tools for risk management. This evolutionary trajectory established the foundation for hedge funds and advanced financial products that characterized the 20th century.

What connects all these stages of financial advancement isn’t just innovation or success — it’s the management of secure private financial communication networks. Whether it was through temple scribes, Roman bankers (argentarii), or encrypted letters of credit from the Templars, successful financial systems have depended on secure, trusted, and exclusive frameworks. The global financial network of the Knights Templar may be the closest historical parallel to today’s Web3 ideals — based on trust, redundancy, semi-autonomous governance, and a vital mission: to empower people and shield them from the overreach of centralized authority.

Today, with Web3 and blockchain technology, we’re positioned to enhance the Templar model into a financial system that is borderless, transparent, and decentralized. Utilizing decentralized infrastructure, Web3 serves to replicate the Templars’ physical outposts — which held assets, facilitated transactions, and provided safe travel — through protocols and smart contracts that operate autonomously on the blockchain. Where the Templars used letters of credit redeemable across continents, Web3 users embrace non-custodial wallets and stablecoins to transfer value globally — independent of banks, borders, or intermediaries.

The Templars utilized cipher systems to safeguard confidential receipts and approvals. In Web3, users rely on zk-SNARKs and sophisticated encryption techniques to verify ownership or identity while maintaining confidentiality — ensuring both privacy and trust. Governance among the Templars was overseen by a central council while allowing for regional autonomy — similar to today’s DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization) structures, which enable communities to collectively manage protocols and financial resources. Additionally, the Templars extended credit to monarchs, accepting land and treasures as collateral — an early version of today’s DeFi lending platforms, where users put up digital assets for automated, collateralized loans governed by smart contracts and algorithmic trust ratings.

For establishing identity and credibility, Templar pilgrims relied on symbols, reputation, and recognition. In the Web3 realm, new decentralized identity frameworks enable users to authenticate their identities without depending on centralized authorities — preserving individual sovereignty while promoting participation in global economies.

By reinstating the moral and structural essence of ancient financial networks through Web3, we are not simply developing new tools — we are reviving a historical mission: to create a trustworthy, decentralized system for value and governance that prioritizes people over power. It’s not just about technical improvements; it’s a spiritual and philosophical journey back to a financial system rooted in transparency, honor, and freedom.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Cryptonews.com. This article aims to provide a general perspective on the subject and should not be construed as professional advice.

The post The Temple of Finance: How History Guides Web3 appeared first on Cryptonews.