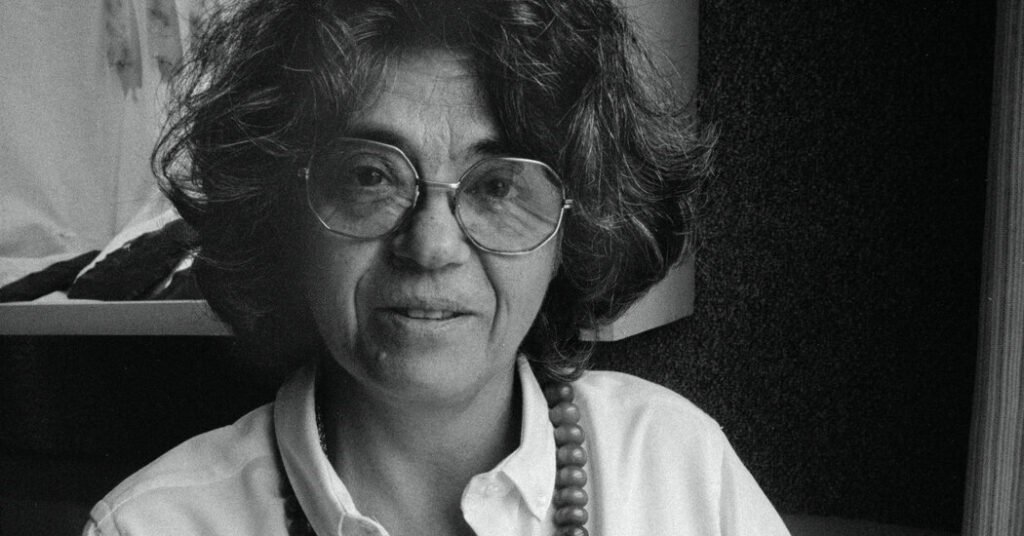

Niede Guidon, a Brazilian archaeologist, made significant contributions that challenged traditional views on how humans first populated the Americas. She played a crucial role in transforming the rugged region of northeastern Brazil into Serra da Capivara National Park. Guidon passed away on Wednesday at her home near the park in São Raimundo Nonato. She was 92 years old.

According to Marian Rodrigues, the park’s director, the cause of death was a heart attack.

Dr. Guidon is best recognized in global scientific communities for her controversial assertion that humans arrived in the Americas over 30,000 years ago. Nevertheless, her achievements in locating and preserving ancient rock art in the challenging, arid landscape of Piauí state are widely respected.

In 1979, due to her advocacy, the Brazilian government designated the area as a national park. By 1991, largely thanks to her efforts, UNESCO named it a World Heritage site. She also played a key role in establishing two museums in the area: The Museum of the American Man, which opened in 1996, and the Museum of Nature, inaugurated in 2018. Furthermore, her influence attracted investments, leading to the construction of a new airport, a federal university campus, and enhanced public education in the region.

Antoine Lourdeau, a French archaeologist who collaborated with Dr. Guidon for about a decade starting in 2006, stated, “To preserve the paintings, it was essential to protect the surrounding environment, which meant providing resources for the local community. Many archaeologists may not fully grasp the social ramifications of their work.”

Dr. Guidon was particularly successful in hiring and training women in a region dominated by men and plagued by domestic violence, as noted by Adriana Abujamra, author of a recent biography of Dr. Guidon. “I’ve heard many heartfelt stories from women who achieved financial independence and left their partners behind,” she explained, using a Portuguese phrase to describe their emancipation.

Beyond her work at the park and museums, many locals produce honey and ceramics, which are sold nationwide through initiatives Dr. Guidon initiated in the 1990s.

Niede Guidon was born on March 12, 1933, in Jaú, a small city in São Paulo State. Although the name Neide is common in Brazil, Niede is not; her father’s family was French, and she was named after the Nied River in France and Germany.

After obtaining a degree in natural history from the University of São Paulo in 1958, Ms. Guidon began teaching in the predominantly Roman Catholic town of Itápolis. However, after exposing corruption in the school to a magazine in early 1959, the town, incited by school administrators, turned against her.

As a single woman who drove a car, avoided Mass, and taught evolution, she became a target in the conservative town. Tensions escalated, and after violent demonstrations, she and two other female teachers were escorted away by police for their safety.

“The scene was almost medieval; all that was missing was a bonfire for witch burning,” she remarked to a reporter at that time, as recounted in a 2024 podcast about her life.

Later that year, she took a position at Paulista Museum in São Paulo, where her interest in archaeology grew. At a photographic exhibition showcasing prehistoric Brazilian rock art, visitors from northeastern Brazil shared images of the paintings in Piauí, which would later become her life’s focus.

However, her first attempt to see the paintings in 1963 was thwarted when a bridge collapsed, cutting off access. The following year, she fled to Paris after receiving a warning that she might be arrested by the military dictatorship that had recently ousted President João Goulart.

In France, she studied archaeology and earned a doctorate from the University of Paris in 1975, though she frequently returned to Brazil for fieldwork. In 1970, Dr. Guidon finally visited the rock paintings in Piauí, and the complexity of the art astonished her; she organized teams to navigate the tough terrain for thorough documentation of hundreds of archaeological sites.

Returning to Brazil for good in 1986, she settled in São Raimundo Nonato, where she was affectionately known as “Doutora,” which means Doctor.

In the 1990s, excavations close to the painting sites revealed artifacts—such as carbon remnants from supposed firepits and stone tools—dated back 30,000 years. Dr. Guidon was amazed, yet many scientists, especially from the U.S., remained skeptical, validating the Clovis model which suggested that humans migrated to the Americas around 13,000 years ago via a land bridge now submerged.

Today, there is broader agreement that humans arrived on the North American continent slightly earlier, yet Dr. Guidon’s discoveries remain contentious. The debate continues over whether the excavated materials were crafted by humans or resulted from natural processes.

Regardless, her efforts significantly highlighted Piauí, securing funding and attention, and even her detractors concede her contributions.

“She was a purpose-driven leader who understood how to influence people,” remarked André Strauss, an archaeologist at the University of São Paulo. While skeptical of some of Dr. Guidon’s claims, he admired her charisma, likening her to “the Churchill of northeastern Brazil.” Like Churchill, she had a knack for the dramatic, often threatening to abandon her endeavors for a more sophisticated life in Paris, as outlined in Ms. Abujamra’s biography.

In the end, she never left. On June 5, she was laid to rest in the garden of her home in São Raimundo Nonato.