Recently, some of the most bizarre mammals on Earth, echidnas, known for their spiny coats and egg-laying habits, have revealed a surprising twist in their evolutionary tale. A new study suggests that these creatures, which scuttle through the underbrush of Australian forests, likely descended from ancestors that lived in water.

This finding challenges previous scientific beliefs about their origins and represents a rare case in evolution, according to researchers.

“Several mammals have transitioned from land to water, but it’s uncommon for a species to adapt back to land,” said Sue Hand, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of New South Wales, during an interview with Live Science.

There are currently four recognized species of echidnas, also referred to as spiny anteaters, all belonging to the Tachyglossidae family. Three species are exclusive to New Guinea, while the fourth is found there as well as throughout Australia.

Historically, scientists believed echidnas and their semi-aquatic cousin, the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), evolved from land-dwelling ancestors, with the platypus lineage eventually taking to the water. Both these animals are monotremes, the only mammals that lay eggs instead of birthing live young.

In an effort to enhance understanding of echidna evolution, Hand and her team revisited a humerus (upper arm bone) from the extinct monotreme Kryoryctes cadburyi, which existed in what is now southern Victoria, Australia, around 108 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period. This species might have been a relative or ancestor of both contemporary platypuses and echidnas, researchers believe.

There has been discussion about whether K. cadburyi was strictly a land animal. Studies of the bone, found at a site called Dinosaur Cove in the early 2000s, showed that it bore similarities to echidna bones.

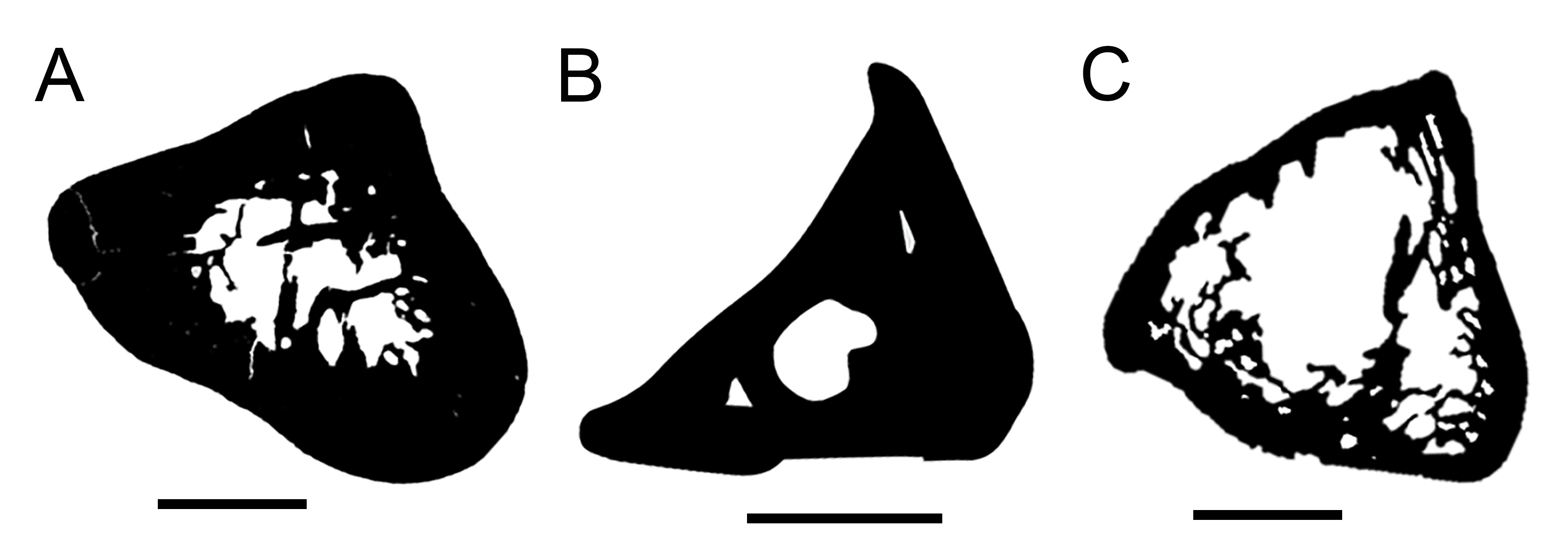

By investigating the outer surfaces of bones, scientists can glean information about how species might be related, Hand explained, but the internal structure provides insights into their lifestyles. Thus, the team employed micro-CT scans to analyze the bone’s internal microstructure.

“Today’s platypuses have very distinct bone characteristics,” Hand noted. “They possess thick bone walls, while echidnas have noticeably thinner walls. We were keen to discover what their common ancestor might have been like.”

Even though the ancient humerus visually resembled an echidna bone, it had thicker walls and a smaller marrow cavity. “We were surprised to find that the internal structure was more similar to that of a platypus than an echidna,” Hand remarked.

The heavier bones would function like ballast, facilitating the animal’s ability to dive underwater. This implies that K. cadburyi was likely a semiaquatic burrower, and that the monotreme lineage was once semiaquatic, the team concluded.

According to the researchers, the ancestors of echidnas eventually transitioned entirely to land, resulting in lighter bones as they adapted to a new lifestyle, as detailed in a study published on April 28 in the journal PNAS.

Due to the scarcity of fossils from the ancestors of echidnas and platypuses, the timeline for this shift to a terrestrial existence remains uncertain. Most of their extinct relatives have only been identified through their teeth and jaws, with the K. cadburyi humerus being the only monotreme limb bone from that epoch discovered so far.

Ready to Switch

Mammals have often adapted from land to a semiaquatic or fully aquatic lifestyle, with examples including whales, dolphins, seals, and beavers, Hand noted. However, it’s extremely rare to see the opposite adaptation.

Nonetheless, semiaquatic burrowers, like today’s platypuses, are ideally suited to thrive in both environments, she added.

Moreover, there are additional indicators of a watery ancestry for echidnas. During their development, echidnas’ beaks contain receptors for detecting minor electrical currents, which similar receptors in other species are often used to locate prey in aquatic settings. Platypuses have a higher concentration of these receptors.

Additionally, the backward-pointing hind feet of echidnas, which are employed for digging, resemble those of platypuses, which use their hind feet to steer while swimming.

“Fossils resembling platypuses date back 100 million years, but the earliest echidna fossils are less than 2 million years old,” noted Tim Flannery, a paleontologist at the Australian Museum in Sydney, who was not involved in this research. “This paper reinforces the idea that echidnas descended from platypus-like ancestors and contributes to a compelling case,” Flannery remarked to Live Science.