Although I know differently, I often can’t help but think if “Afghanistan” might stem from an ancient term meaning “tragedy.”

Afghanistan is once again making news — quickly and with little opposition, it has fallen under the control of the Taliban, who aspire to establish a medieval-style caliphate. For those of my generation, the events of this weekend evoke a sense of déjà vu from years of watching this troubled region. In the 1980s, Afghanistan brought the USSR to its knees over nearly a decade of conflict. Now, after two decades of American involvement, costing nearly a trillion dollars and countless lives, the USA seems to be learning that this spirited nation resists outside rule.

It’s easy to assign blame: Did George W. Bush make a mistake by invading in 2001? Was it wrong for Donald Trump to negotiate with the Taliban in early 2020? Should Joe Biden have withdrawn troops so hastily? In the end, however, no one truly knows the answers…which is precisely why we keep finding ourselves facing the same issues.

One truth stands out: The repeated inability of powerful nations to impose their will on the Afghan populace underscores our ethnocentrism and a failure to grasp their motivations. Leveraging Afghanistan for political gains in the U.S. sidesteps the devastating human impact of the instability affecting Afghans for decades.

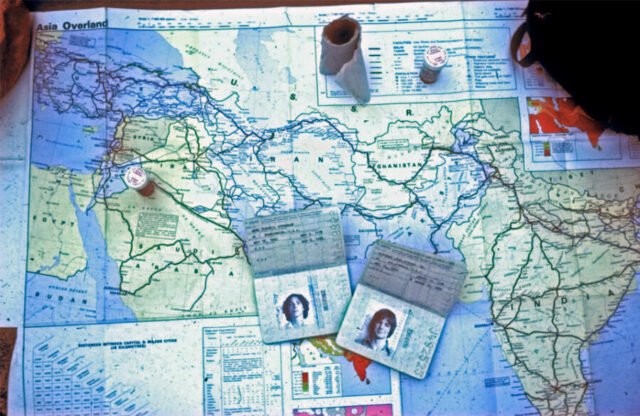

For me, this tragedy is even harder to witness because of the meaningful connections I’ve made with people in Afghanistan. As I watch the news, memories flood back from my 1978 journey along the “Hippie Trail” from Istanbul to Kathmandu when I was just 23. It was an unforgettable adventure — one that’s nearly impossible now. Each border crossing was a mini-drama, and every stop turned into a cherished memory.

At the Iran-Afghanistan border, surrounded by abandoned VW vans that guards had dismantled looking for drugs, we were careful to keep our backpacks in our laps to avoid anyone sneaking something illegal in. We waited for a doctor to check our vaccinations. My travel companion, Gene, needed a shot, and I vividly recall how the needle bent as it struggled to pierce his skin.

Once we set out for Herat in our crowded minibus, the driver unexpectedly stopped, pulled out a knife glimmering in the sun, and declared, “Your tickets just got more expensive.” An Indian traveler calmed our uproar, and we all reluctantly handed over the extra fee.

In Herat, a cultural hub in western Afghanistan, we watched chariots lit by torches race through the night from our hotel’s rooftop. Each day unfolded like an adventure — not in terms of tourist attractions, but through exploring bustling markets and quiet gardens. This was shortly after a coup supported by the USSR. We noticed a Soviet tank positioned in the central square, and restaurants had their menus slashed with a note: “Thanks to Soviet liberation.”

Our bus traversed what might have been Afghanistan’s only paved road, a product of foreign aid, showcasing a desolate landscape. I remember the monotonous scenery occasionally broken by cemeteries, desolate collections of crooked tombstones scattered across the desert. Even with 50 passengers, our restroom breaks were swift: the bus would halt, men would disembark on one side while women would gather on the other, squatting in their large black robes.

Truck stops seemed primarily for the driver to indulge in hashish. At one point, I witnessed a group of men squatting together, sharing whatever they were smoking while watching a goat being skinned.

Kabul was the only real city, appearing to exist merely as a center to govern from — a necessity in a country that seemed uncertain about urban life. I saw people in uniforms that looked as though they’d only ever known tribal attire.

While dining at a backpacker’s cafeteria, a man approached my table and asked, “May I join you?” I replied, “You already are.” He inquired, “Are you American?” I confirmed, “Yes.”

Then he launched into a rehearsed speech: “I’m a professor here. I want you to understand that around the world, one-third of people eat with spoons and forks like you, one-third with chopsticks, and one-third use their hands. And we are all civilized regardless.”

This interaction ended up being one of the most profound moments of my life — like every other part of my journey in Afghanistan, it challenged my ethnocentric views and reshaped my cultural understanding.

Crossing into India through the renowned Khyber Pass marked a highlight of any overland trip. We were nervous Westerners on the bus, our bags on our laps, realizing we were nearing India, which felt strangely like going home. Our bus ticket included a “security supplement” to ensure safe transit through the region ruled by independent tribes. Gliding under their stone fortifications, adorned with tattered flags and guarded by bearded sentinels clutching old rifles, I was relieved to have paid extra for that safety.

As we emerged from the harsh mountains of Afghanistan, the landscape opened into a vast and humid plain. The rocky terrains of Iran and Afghanistan faded behind us, while ahead lay a billion people across Pakistan and India.

With this entry, I’m launching a week-long series of posts featuring photos from my journey and snippets from my 1978 journal documenting my adventures through Afghanistan. (This essay springs from distant memories; upcoming posts were penned nightly, recounting the day’s explorations in this captivating land.) Stay tuned, and keep the Afghan people in our thoughts and prayers.