The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently approved a blood test that can identify indicators of Alzheimer’s disease in the brain, based on several studies. This marks the first blood test available for this prevalent type of dementia.

Let’s explore how this new blood test functions and its potential benefits for patients.

Why is a blood test for Alzheimer’s necessary?

Alzheimer’s disease is increasingly prevalent, partly due to the larger aging population. In the U.S., it is estimated that by 2025, 7.2 million Americans aged 65 and older will be living with Alzheimer’s dementia. The likelihood of being affected rises with age: around 5% of individuals aged 65 to 74 have Alzheimer’s, while over 33% of those aged 85 and above are affected.

Once a doctor confirms cognitive decline in a patient, this blood test can serve as an alternative to traditional diagnostic procedures. Historically, standard methods for diagnosing Alzheimer’s have been intrusive and costly, often requiring positron emission tomography (PET) scans that utilize radioactive materials or lumbar punctures (spinal taps) to extract spinal fluid. Doctors sometimes also use MRIs or CT scans to eliminate other potential causes of cognitive decline.

This new test analyzes the ratio of two proteins in the blood, which correlates with the presence of amyloid plaques— a crucial indicator of Alzheimer’s found in the brain.

For individuals experiencing memory issues potentially linked to Alzheimer’s, the first step is consultation with their primary care physician (PCP), who will conduct a cognitive assessment. If cognitive decline is evident, the patient will be referred to a neurologist for further evaluation.

Both dementia specialists and PCPs can order this blood test to assist in diagnosis, according to Dr. Gregg Day, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, who spearheaded a study related to the blood test published in the Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. A 2024 study in JAMA found that the accuracy of the test remains consistent regardless of whether it is ordered by a PCP or a specialist.

PCPs may utilize the test results to determine whether to refer patients to a specialist, who could suggest treatments like lecanemab or donanemab, mentioned Day. Alternatively, a PCP might prescribe a medication such as donepezil, known to enhance cognitive function in Alzheimer’s patients. Following FDA approval, it is anticipated that Medicare and private health insurance will cover the cost of the new blood test, according to Day.

Who is eligible for the blood test?

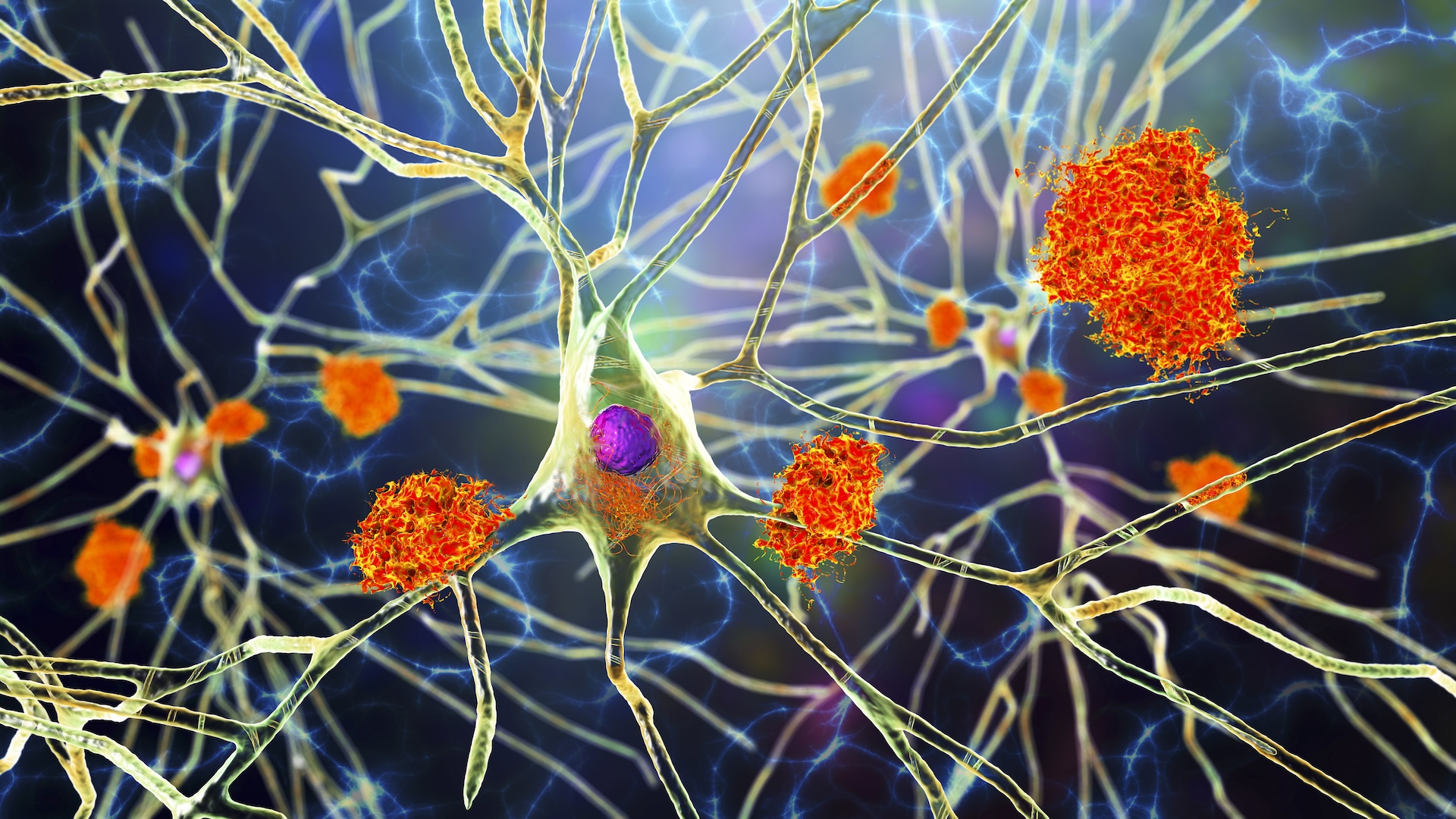

The test, known as the “Lumipulse G pTau217/ß-Amyloid 1-42 Plasma Ratio,” is meant for individuals aged 55 and above who display signs and symptoms of cognitive decline confirmed by a healthcare professional. This test aims to detect amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease early on. (Amyloid plaques are abnormal protein clumps found between brain cells.)

Related: Man nearly guaranteed to get early Alzheimer’s is still disease-free in his 70s — how?

Early identification is crucial, stated Dr. Sayad Ausim Azizi, clinical chief of behavioral neurology and memory disorders at the Yale School of Medicine. The Alzheimer’s-influenced brain resembles a deteriorating engine; the plaque acts similarly to rust, obstructing the engine’s functioning, Azizi explained to Live Science.

There are FDA-approved treatments akin to oil that assist the engine, but they do not eliminate the rust itself, he added. Current therapies can slow brain deterioration by approximately 30% to 40%, research indicates, enabling patients to maintain functional abilities for an extended period.

“If you’re currently active and living independently, and you skip medication, you might struggle to manage daily tasks in five years,” Azizi posited as a hypothetical scenario. “However, if you take the medication, you could extend that timeframe from five years to eight.” Proper implementation of the new blood test could facilitate earlier access to these treatments for more individuals.

Can this blood test serve as a general screening method?

The test is not designed for general screening of the population. It is exclusively intended for individuals diagnosed by a medical professional with symptoms indicative of Alzheimer’s disease, according to Day and Azizi.

Some presence of amyloid occurs in the brain as part of normal aging, so detection does not imply a future Alzheimer’s diagnosis. If the test indicates amyloid plaques 20 years before any cognitive symptoms arise, Azizi clarified, initiating treatment at that moment would not be practical.

“The treatments are not completely risk-free,” he warned. For instance, individuals receiving lecanemab need to undergo infusions every two weeks initially, gradually transitioning to every four weeks. Donanemab is administered every four weeks. Both medications have potential side effects like headaches, nausea, and vomiting related to the infusion.

In rare cases, donanemab may trigger serious allergic reactions, and both lecanemab and donanemab have been associated with uncommon incidents of brain swelling or bleeding. These adverse effects are linked to “amyloid-related imaging abnormalities,” which manifest in brain scans.

Is there a chance of false positives?

The new test can yield false positives, implying that a person may test positive for Alzheimer’s when they do not have the condition. This occurs because the amyloid indicators the test measures might also link to other medical issues. For example, amyloid accumulation could indicate kidney dysfunction, Day suggested, which is why he advises performing a kidney function test alongside the Alzheimer’s blood test.

The Mayo Clinic study examined approximately 510 participants, 246 of whom exhibited cognitive decline. The blood test confirmed 95% of those with cognitive symptoms had Alzheimer’s. However, about 5.3% of cases returned false negatives, while 17.6% indicated false positives, Day reported.

Most patients with false-positive results presented Alzheimer’s-like changes in their brains, yet their symptoms were ultimately connected to other conditions, such as Lewy body dementia, Day noted. The research highlighted that the blood test effectively differentiates Alzheimer’s from other dementia types.

As with many clinical trials, the study populations were primarily healthier than average, noted Day. These individuals were not only in better overall health but also more likely to possess health insurance and identify as white and non-Hispanic.

When the blood test is applied to a broader population, those with conditions like sleep apnea or kidney disease might test positive without having Alzheimer’s. Some individuals with these health issues may also experience cognitive difficulties unrelated to Alzheimer’s. If the blood test suggests potential amyloid increase, healthcare providers might pursue further testing and inquire about the patient’s sleep patterns to eliminate other explanations.

Could this blood test enhance Alzheimer’s research?

This test will enable researchers to better understand the relationship between clinical symptoms and blood test outcomes, according to Azizi. “This is an excellent means of utilizing a biomarker [measurable disease indicator] in the blood to facilitate earlier diagnoses, which can lead to intervention with medications to slow disease progression,” he said.

Azizi also stated that this blood test could assist in monitoring the effectiveness of Alzheimer’s treatments, benefiting patients on currently approved drugs as well as those participating in clinical trials for new therapies. In the future, researchers are also expected to explore the efficacy of blood-based testing across a broader array of populations, Day noted.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.